Nagpur Today Theatre Article By Sanjay Wankar: If these arguments have any validity, then clearly a determined revision is necessary of our attitude towards the stage of today. That the theater ought not servility to follow cinematic methods seems unnecessary of proof, even although we may admit that certain devices of the film may profitably be called into service by playwright and director. She Loves Me Not with ample justification utilized for the purpose of stage comedy a technique which manifestly was inspired by the technique strictly proper to the cinema, and various experiments in the adapting of the filmic flash-back to theatrical requirements have not been without significance and value. But this way real success does not lie; the stage cannot hope to maintain its position simply by seizing on novelties exploited first in the cinema and in general we must agree that the cinema can, because of its peculiar opportunities, wield this technique so much more effectively that its application to the stage seems thin, forced and artificial.

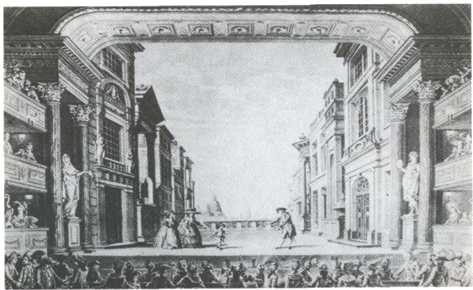

AMSTERDAM 18TH CENTURY

This, however, is not the most serious thing. Far more important is the fundamental approach which the theatre during recent years has been making toward its material. When the history of the stage since the beginning of the nineteenth century comes to be written with that impartiality which the viewpoint of distant time can provide, it will most certainly be deemed that the characteristic development of these hundred odd years is the growth of realism and the attempted substitution of naturalistic illusion in place of a conventional and imaginative illusion.

In the course of this development stands forth Ibsen as the outstanding pioneer and master. At the same time, this impartial survey may also decide that within the realistic method lie the seeds of disruption. It may be recognized that, while Ibsen was a genius of profound significance, for the drama Ibsenism proved a curse upon the stage.

The whole realistic movement which strove to impose the conditions of real life upon the theatre may have served a salutary purpose for a time, but its vitality was but short-lived and, after the first excitement which attended the witnessing on the stage of thins no one had hitherto dreamt of putting there had waned, its force and inspiring power was dissipated. Even if we leave the cinema out of account, we must observe that the realistic theatre in our own days has lost its strength. No doubt, through familiarity and tradition, plays in this style still prove popular and popular success being the first requirement demanded of dramatic art, we must be careful to avoid wholesale condemnation; Tobacco Road and Dead End are things worthy of our esteem, definite contributions to the theatre of our day. But the continued appearance and success of naturalistic plays should not confuse the main issue, which is the question whether such naturalistic plays are likely in the immediate future to maintain the stage in that position we should all wish it to occupy.

Facing this question fairly, we observer immediately that plays written in these terms are less likely to hold the attention of audiences over a period of years than are others written in a different style; because bound to particular conditions in time and place.

They seem inevitably destined to be forgotten, or, if not forgotten, to lose their only valuable connotations. Even the dramas of Ibsen, instinct with a greater imaginative power than many works by his contemporaries and successors, do not possess, after the brief passing of forty years, the same vital significance they held for audiences of the eighties and nineties.

If we seek for and desire a theatre which shall possess qualities likely to live over generations, unquestionably we must decide that the naturalistic play, made popular towards the close of the nineteenth century and still remaining in our midst, is not calculated to fulfill our highest wishes.

Of much greater importance, even, is the question of the position this naturalistic play occupies in its relations to the cinema. At the moment it still retains its popularity, but, we may ask, because of cinematic competition, is it not likely to fail gradually in its immediate appeal?

The film has such a hold over the world of reality, can achieve expression so vitally in terms of ordinary life, that the realistic play must surely come to seem trivial, false and inconsequential. The truth is, of course, that naturalism on the stage must always be limited and insincere. Thousands have gone to The Children’s Hour and come away fondly believing that what they have seen is life; they have not realized that here too the familiar stock figures, the type characterizations, of the theatre have been presented before them in modified forms.

From this the drama cannot escape; little possibility is there of its delving deeply into the recesses of the individual spirit. That is a realm re-served for cinematic exploitation, and, as the film more and more explores this territory, does it not seem probable that theatre audiences will become weary of watching shows which, although professing to be “lifelike,” actually are inexorably bound by the restrictions of the stage? Pursuing this path, the theatre truly seems doomed to inevitable destruction.

Whether in its attempt to reproduce reality and give the illusion of actual events or whether in its pretence towards depth and subtlety in character-drawing, the stage is aiming at things alien to its spirit, things which so much more easily may be accomplished in the film that their exploitation on the stage gives only an impression of vain effort.

Is, then, the theatre, as some have opined, truly dying? Must it succumb to the rivalry of the cinema? The answer to that question depends on what the theatre does within the next ten or twenty years. If it pursues naturalism further, unquestionably little hope will remain; but if it recognizes to the full the conditions of its own being and utilizes those qualities which it, and it alone, possesses, the very thought of rivalry may disappear.

Quite clearly, the true hope of the theatre lies in a rediscovery of convention, in a deliberate throwing-over of all thoughts concerning naturalistic illusion and in an embracing of that universalizing power which so closely belongs to the dramatic from when rightly exercised. By doing these things, the theatre has achieved greatness and distinction in the past.

We admire the playhouses of Periclean Athens and Elizabethan England; in both a basis was found in frank acceptance of the stage spectacle as a thing of pretence, with no attempt made to reproduce the outer forms of everyday life. Conventionalism ruled in both, and consequently out of both could spring a vital expression, with manifestations capable of appealing not merely to the age in which they originated but to future generations also.

Precisely because Eschylus and Shakespeare did not try to copy life, because they presented their themes in highly conventional forms, their works have the quality of being independent of time and place.

Their characters were more than photographic copies of known originals; their plots took no account of the terms of actuality; and their language soared on poetic wings. To this again must we come if our theatre is to be a vitally arresting force. So long as the stage is bound by the fetters of realism, so long as we judge theatrical characters by reference to individuals with whom we are acquainted, there is no possibility of preparing dialogue which shall rise above the terms of common existence.

From our playwrights, therefore, we must seek for a new foundation. No doubt many journeymen will continue to pen for the day and the hour alone, but of these there have always been legion; what we may desire is that the dramatists of higher effort and broader ideal do not follow the journeyman’s way.

Boldly must they turn from efforts to delineate in subtle and intimate manner the psychological states of individual men and women, recognizing that in the wider sphere the drama has its genuine home. The cheap and ugly simian chatter of familiar conversation must give way to the ringing tones of a poetic utterance, not removed far off from our comprehension, but bearing a manifest relationship to our current speech.

To attract men’s ears once more to imaginative speech we may take the method of T. S. Eliot, whose violent contrasts in Murder in the Cathedral are intended to awaken appreciation and interest, or else the method of Maxwell Anderson, whose Winter set aims at building a dramatic poetry out of common expression. What procedure is selected matters little; indeed, if an imaginative theatre does take shape in our years, its strength will largely depend upon its variety of approach.

That there is hope that such a theatre truly may come into being is testified by the recent experiments of many poets, by the critical thought which has been devoted to its consummation and by the increasing popular acclaim which has greeted individual efforts.

Established on these terms native to its very existence and consequently far removed from the ways of the film, the theatre need have no fear that its hold over men’s minds will diminish and fail. It will maintain a position essentially its own to which other arts may not aspire.

By Sanjay Wankar